A man and his dog one day decided to go on a pilgrimage together.

A man and his dog one day decided to go on a pilgrimage together.

They headed north towards Kuan yin yuan in the Chao province of China where the great Chan (Chinese Zen) master Zhaouzhou, aka Joshu, was said to reside.

The man hoped to have an audience with this venerable guru who was now in his nineties. He hoped to finally lay to rest some of his most pressing doubts and worries.

After months of arduous travel, he arrived at Zhaouzhou’s temple and sat down with the great teacher, his four-legged companion at his side.

Bowing, he put forward the question that he had been wrestling with for as long as he could remember: “Tell me,” he said, “does my dog have a soul?”

Zhaouzhou looked at the dog, then back to the pilgrim, and gave his reply: “No.”

This is my slightly beefed up version of the Mu Koan, which in its original, much more concise form, reads more like a knock-knock joke rather than the fable I’ve presented to you, trying as I have to fill in some of the historical background at the same time.

Here’s the ur-koan:

A monk asked Joshu, “Has a dog Buddha Nature?” Joshu answered, “Mu.”

“Knock, knock.”

“Who’s there?”

“Mu.”

“Mu who?”

“Just Mu.”

Mu in Japanese (in Chinese, Wu, which is the language Zhaouzhou/Joshu would have spoken) can be translated in a number of ways: has not; without; does not. Or just plain and simple NO, which as translations go, also benefits from having the singular syllabic clout of the original.

Buddha nature I’ve translated above as “soul”. I think this is because for you, me, Joshu, Plato, as well as the pilgrim in question, we would all agree that what is being referred to is some kind of essence, or life-force. It would probably also help to know that the pilgrim is asking Joshu a question that already has a doctrinal (and so, in some sense, a definitively settled) provenance.

That is: the Lotus Sutra, written a thousand years before their colloquy, but also the Nirvana Sutra, both state, without question that “all sentient beings are endowed with Buddha nature”. So if the matter is cut-and-dried to this scriptural degree, why even faff around with such a query?

Wouldn’t this be like asking the Pope: “Was Christ really the perfect, full and definitive revelation of God here on earth?”

Wouldn’t this be like asking the Pope: “Was Christ really the perfect, full and definitive revelation of God here on earth?”

Or asking Picasso: “Does art have a function in our lives?”

Or Barak Obama: “Can an individual make a difference to the world around him or her?”

We’d expect all three to respond along the lines of “Does a bear shit in the woods?” but imagine the answer being not just a negation of the self-evident principle, but a seemingly all-conclusive NO.

That would be one effect of Mu, which regardless of the form the question, it takes, has somehow bedevilled, bekindled, becoruscated spiritual seekers for almost a thousand year.

“Why?”, you might be asking yourself at this point, not particularly bedevilled, bekindled, becoruscasted, or even bemused. At first glance, doesn’t Mu read a bit like a shaggy dog story, a somewhat hollow narrative anti-climax?

“Why?”, you might be asking yourself at this point, not particularly bedevilled, bekindled, becoruscasted, or even bemused. At first glance, doesn’t Mu read a bit like a shaggy dog story, a somewhat hollow narrative anti-climax?

“But look again,” advises Philipino Jesuit Priest turned Zen master Ruben L.F. Habito: “This is a monk asking not a doctrinal question, but in all earnestness, as a matter of life and death. The response he gets from the Zen master is likewise a response that cuts right through this matter of life and death: MU!”

Equally, this man (me) is now asking a variation on this question, in all earnestness, a question first posited to me by Massimo 20 years ago. Something like: can a dog teach us to be “better” versions of ourselves, i.e. to be more in touch with our souls by engaging in day-to-day contact with theirs? Is that what we’re doing with the animals in our lives, with the dogs and cats, and other human-animals too? Is this what it all boils down to? And if it does boil down to this, what do we do with this boiled-down psycho-spiritual consommé?”

Let’s get this straight, whatever your first take on it, Mu is the first koan. Just like “In the beginning there was nada” is the first line of most holy books. It comes out of nowhere, so we’re not really sure where it’s going, or if it’s even going. It is also the first because it is, and was, the first to be presented in what is seen by some as The Koan Bible called The Gateless Gate, or Gateless Barrier.

Let’s get this straight, whatever your first take on it, Mu is the first koan. Just like “In the beginning there was nada” is the first line of most holy books. It comes out of nowhere, so we’re not really sure where it’s going, or if it’s even going. It is also the first because it is, and was, the first to be presented in what is seen by some as The Koan Bible called The Gateless Gate, or Gateless Barrier.

The Gateless Barrier was compiled in the 13th Century by a monk called Wumen Huikai (in Japanese for you, dear Google bot: Mumon Ekai) who himself spent 6 years tussling with Mu koan after it was first presented to him by his teacher Gatsurin Shikan.

He writes about his own experience with Mu as the equivalent of “swallowing a red-hot iron ball, which you cannot spit out even if you try”. Living with Mu (No), he writes, requires us to “arouse our entire body with its three hundred and sixty bones and joints, its eighty-four thousand pores of the skin; [and] summon up a spirit of great doubt, concentrating on No continuously, day and night.”

What is this “spirit of great doubt” he talks about? It is the doubt, I guess, of living, as we all do, caught between a rock and a hard place; between the duality of Yes and No, of Safety/Danger, of Listened-to/Ignored, of Loved and Neglected. Am I to buy into (i.e. believe) one or the other? If either, which? If neither, what?

What is this “spirit of great doubt” he talks about? It is the doubt, I guess, of living, as we all do, caught between a rock and a hard place; between the duality of Yes and No, of Safety/Danger, of Listened-to/Ignored, of Loved and Neglected. Am I to buy into (i.e. believe) one or the other? If either, which? If neither, what?

The Japanese word koan translates as “public case”, or legal precedent. But this is not an ex post facto “collective body of judicially announced principles”, delivering the outcome of a contemplative process or dialogue. Instead, a koan is more of a dynamic, DIY phenomenon, giving us the tools to work through the case ourselves, with materials supplied from our own lives.

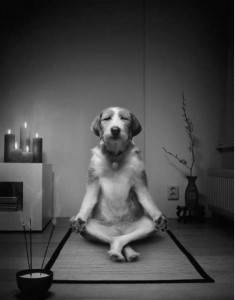

Zenkei Shibayama points out another etymological reading of the word as a place rather than a case, a place where the truth might reside. A teacher presents the koan as a potential site for truth, and some basic tools to the student, who is then encouraged to excavate. The tools for me here are: paper, pen, computer, and online WordPress platform. The materials: a dog called Max, and the life we share.

The student then digs. She digs, and digs, and digs, and digs. At some point perhaps she plants seeds, or writes a blog post, or makes a drawing, or creates a garden, whatever she needs to do in order to understand more about the place, the place where she digs in order to find truths, but also to make the place/koan, her own; to make of a universal truth her own truth.

The student then digs. She digs, and digs, and digs, and digs. At some point perhaps she plants seeds, or writes a blog post, or makes a drawing, or creates a garden, whatever she needs to do in order to understand more about the place, the place where she digs in order to find truths, but also to make the place/koan, her own; to make of a universal truth her own truth.

I initially wrote “to get to the bottom of the truth”, but of course, unless we dig all the way through to China, and even then, we already know there is no bottom to there, maybe even no there there, as Getrude Stein once memorably said of her childhood city, Oakland.

The koan cannot be treated as a mathematical problem. Rather in this bottomless site, we continue to dig, for months, or years, or a lifetime; for as long as it takes until we alight on something that smells, or looks, or even more importantly feels like a necessary truth to us, even just in that moment; but not only for us, for our teacher too, the one who first took us to this place.

Let’s look at some other analogies for what kind of tool the humble koan most resembles. Maybe a sledgehammer, as Zenkei Shibayama would have it, “to smash our dualistic consciousness, and open our inner spiritual eye”? Or maybe it works in a more pinpointed way, as Philip Kapleau suggests, a kind of drill, boring holes through all our flimsy certainties, the drill “bit” having at its very tip a single diamantine word, Mu?

Let’s look at some other analogies for what kind of tool the humble koan most resembles. Maybe a sledgehammer, as Zenkei Shibayama would have it, “to smash our dualistic consciousness, and open our inner spiritual eye”? Or maybe it works in a more pinpointed way, as Philip Kapleau suggests, a kind of drill, boring holes through all our flimsy certainties, the drill “bit” having at its very tip a single diamantine word, Mu?

Koans need not necessarily involve smashing, drilling, or obliterating -spiritual orthodontry, existential plastic surgery- breaking bones in order to reshape them.

The Mu koan, writes James Ishmael Ford in his essay On The Utter, Complete, Total Ordinariness of Mu, can, and often does, feel like “a nagging something in the back of your head…a small pebble in your shoe…the longing inhabiting your dreams”, but it can also be encountered “like a blueberry found on a bush. You can just reach out, pick it, and throw it into your mouth.”

John Tarrant, who also writes deftly about Koans agrees with this, stating that Mu is “confusing, irritating, mysterious, beautiful, and freeing, a gateway into the isness of life, where things are exactly what they are and have not yet become problems”.

John Tarrant, who also writes deftly about Koans agrees with this, stating that Mu is “confusing, irritating, mysterious, beautiful, and freeing, a gateway into the isness of life, where things are exactly what they are and have not yet become problems”.

I’m hoping that Mu can be taken home in a cardboard box, like I took Max home from the pet shop, who earlier on in the day was sleeping cuddled up next to his sister, and now cries a little from the crate I’ve put him in to spend his first night alone, even though he’s not completely alone as I am sleeping in the same room with him, just a few feet away.

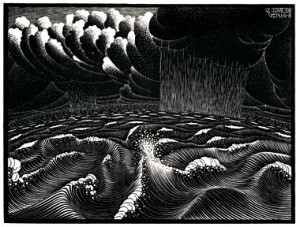

I’m also hoping, to use anther Tarrant analogy, that this koan can be for me a kind of lantern as I head into the winter of 2015, a season in which I often struggle with the day-to-day more than at other times.

“You can think of koans as vials full of the light that the ancestors walked through,” Tarrant proposes in the Foreword to a collection of essays on Mu that I’ve begun to read. “And if you can get these vials open you share that light,” he writes encouragingly.

“You can think of koans as vials full of the light that the ancestors walked through,” Tarrant proposes in the Foreword to a collection of essays on Mu that I’ve begun to read. “And if you can get these vials open you share that light,” he writes encouragingly.

“By getting them open I mean you get at the light any way you can—you find the key and open the vials with a click, break them, drop them from a height, sing to them, step inside them, shake them so that some of the light spills out. Then that light is available to you, which might be handy if you’re ever in a dark and twisty passage.”

The passage is always a little (or a lot) dark and twisty, isn’t it? It is for me as I head into winter. What difference will Max and Mu make to it? Let us see.

The passage is always a little (or a lot) dark and twisty, isn’t it? It is for me as I head into winter. What difference will Max and Mu make to it? Let us see.