I am writing all of this with Donald Trump, the reality television host, and very angry property tycoon, getting closer and closer to the Whitehouse. A few months before Max comes into my life, Trump announces that he has decided to run for President with this wall-building vow:

I am writing all of this with Donald Trump, the reality television host, and very angry property tycoon, getting closer and closer to the Whitehouse. A few months before Max comes into my life, Trump announces that he has decided to run for President with this wall-building vow:

“I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words.”

Like a lot of spiritually-focused liberals, I don’t pay much attention to Trump’s bricks-and-mortar threats or promises when they are made. I am much more involved in my own wall, my more abstract Mu-wall, jutting out as it does from the depths of navel, 2,000 miles long, 10 feet high, or more, coated in anti-climb paint, topped with barbed wire and jagged glass shards.

It is not perhaps by chance that Mu is the first koan in the collection “The Gateless Gate” or “Gateless Barrier”. Mu seems to stand at the entrance to a place we might have thought was once unbarred, but is now frustratingly off-limits.

All my patients stand before a Mu-wall and wonder how they’re going to scale it. I do too. With them. For them. For myself.

The wall affects us, broadly speaking, in three ways. We worry about it (anxiety), we get angry with it (frustration and rage), and we feel hopeless about it (depression).

In the years I spent meditating in Rome as part of Michele’s zen posse, I must have spent hundreds of hours looking at wall 2 feet in front of my eyes at L’Arco where we held our morning and evening sessions. Walls, both figuratively and literally, were objects of contemplation for me on a daily basis, and yet not once did I actually think about what these walls meant to me, or me to them.

Lucius Domitius Aurelianus (born 9 September 214, or 215), the Trump of his day, ruled Rome for only 5 years (270-275), being murdered, as all good Roman Emperors eventually are, on his way to Persia.

One of the projects of his 5 year reign was that of giving the go-ahead to his army for them to build a 12 mile wall around the city, 3.5 metres thick, 8 metres high. This enclosed an area of 5.3 square miles, built as a response to the crisis of barbarian tribes flooding into Northern Italy in the third century via the Germanic frontier. The walls were hastily constructed, an emergency measure, not built to last. But they did though, almost 2,000 years, serving as Rome’s primary fortification until the 19th century. These walls, with their square towers ever 1000 Roman feet (29.6 metres) were those I would see when I looked out from the 11th floor of our flat everyday onto the city below.

“Certain strategic flaws in the design and construction of the walls,” writes the historian Alaric Watson, “point to the lack of experience…on the part of the workmen involved…indicating that the function of the walls was as much a psychological deterrent as a physical barrier.”

Are not all walls, from Hadrian’s, and The Great Wall of London, built respectively 150 and 70 years earlier, onwards, not psychological defences too? Is not Trump’s. His wall stands as a symbol for keeping jobs inside the borders of America, but also for keeping the social problems facing his country out:

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…..They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

The neurological objective correlative to the wall is a synaptic chain primed by chemical in the brain (norepinephrine, acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin) and body (hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol) which are designed to keep at bay danger and threat as perceived by areas of the limbic system.

Freud was one of the first thinkers to see our inner barricades. When threatened, he signalled two responses that we might take: Verdrängung (driving out, displacement, repression, suppression) and Abwehren (defence, resistance, warding off). The two are often intertwined. Freud himself got driven out of Vienna by Hitler’s use of Verdrängung, perceiving the Jews as a threat, a kind of “virus” or “parasitic force” to the Reich Volk. Although the walls and fences of Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen were probably more in line with Abwehren.

Freud was one of the first thinkers to see our inner barricades. When threatened, he signalled two responses that we might take: Verdrängung (driving out, displacement, repression, suppression) and Abwehren (defence, resistance, warding off). The two are often intertwined. Freud himself got driven out of Vienna by Hitler’s use of Verdrängung, perceiving the Jews as a threat, a kind of “virus” or “parasitic force” to the Reich Volk. Although the walls and fences of Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen were probably more in line with Abwehren.

Abwehren is a stationary No, a kind of shield. Verdrängung is more active No, removing something that might feel dangerous or threatening from conscious experience, to another place, a place of exile, the so-called unconscious, where we no longer have to face it. Out of sight, out of mind.

Both are manifestations of Mu.

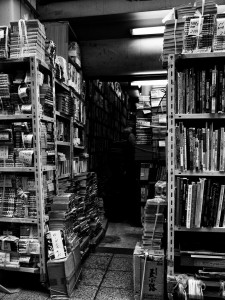

This is what the Mu-wall looks like:

NONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONONO

Or:

MUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMUMU

But like Lucius Domitius Aurelianus’s wall, between each brick, each letter, a space through which we might crawl, or walk, or think our way through. Within the bricks themselves, bricks being like bodies: expanded clay aggregate, a mix of fine-grained natural rock, soil material, minerals, and traces of metal oxides and organic matter. On an atomic level, even more space, all is gateless. But try telling that to someone stuck on one side of their koan dilemma.