A visitation from the Chicken of Depression is a profoundly Mu moment. It is a moment where something punitive in us steps back and looks at the lopsided, cracked, object-strewn nature of our less than perfect lives, our less than perfect manuscripts, and finds something abject, debased and deficient therein.

A visitation from the Chicken of Depression is a profoundly Mu moment. It is a moment where something punitive in us steps back and looks at the lopsided, cracked, object-strewn nature of our less than perfect lives, our less than perfect manuscripts, and finds something abject, debased and deficient therein.

It comes without fail for me a couple of pages, or sometimes a couple of months into working on a creative project, when the grace and sufficiency of the work becomes eclipsed by a force that calls the whole endeavor into question. It can also come six months into any new relationship, or friendship.

Mu is suddenly all-pervasive, like a painful rash exposed to the elements through threadbare garments. These garments, these pages of writing, are (for me) objects that try to swaddle my fragility, my animality, my nerve-laden self, so responsive to ideas and pleasurable stimulation, but also so sensitive to abrasions, physical as well as emotional. Now here is Mu whispering in my ear that there are no eyes outside of this book – perhaps because of the way I am writing it, because of what I’m writing about, that it will never be sought after or read. So why bother? The writing, and everything that supports it, is an empty gesture, Mu claims. “Your every thought, and word, and hope, and desire empty, pointless, dead on arrival.”

It’s a penny-drop moment. But not a satisfying drop. Not the sliding into place of a puzzle piece in a section of undifferentiated green (grass, hills, dress), but more like the drop into the empty void that should have been the floor of a restaurant, or the skid, and tumble and drop that follows a hiking accident. Like that of Aron Ralston on April 26, 2003, who whilst out hiking alone through Blue John Canyon, in eastern Wayne County, Utah, fell and dislodged a boulder which came crashing down after him, crushing and wedging one of his hands against the wall of the crevice he’d fallen into, creating an inescapable mantrap.

That is the moment when Mu has you good, has you through and through, consummately, utterly, body and soul. The moment where Mu has found some activity or aspect, or situation in your life that is more contingent than others. This is where Mu gets to work, jumping straight in, dissolving all the fantasies and mindtrips we use to buttress and fortify this resource for meaning and value, calling into question our most cherished beliefs about this thing, this project, be it a job, or a house, or a child, or a dog, or a book we’re writing, whatever it is onto which we affix our sense of identity and self-worth, there Mu gets to work, like clothes moths burrowing into the fibres of your favourite jumper.

Why does it undermine the writing for me? Perhaps because I have always relied on writing as well as other creative activities as a means of explaining myself to myself, as a way to get flow and focus into my life, a meaning-rich filler to each day, the protein content of the domestic sandwich. Which is not to say that I don’t value or appreciate the bread and butter of life (working with clients, looking after Max, my partner, gardening, housework, walks), but a day without writing feels like a sandwich that has no filling. In this case, which is where Mu finds a spot to burrow in, I am confused to what extent I am the sole eater of my sandwiches, or if I am in fact making them for other people. And if so, am I making a good enough sandwich, or are these shit sandwiches, literally to some extent, which only I have any interest in reading and writing.

The interesting thing about empty-filling Mu is that it doesn’t seem to settle on autotelic activies (from the Greek autos, “self” and telos, “goal”). That’s to say, activities that we do as an end in themselves, and we have scant need for these activities to be recognised or celebrated by others, or at least by others outside our immediate social circle. Everything in my life sandwich, other than the writing feels quite autotelic, but writing is the one heterotelic activity. Heterotelic: (heteros, “another”, and telos, “end, goal”). Only writing, for me has this conscious or implied reference to the accomplishment of some end, to recognition and approval in the eyes of the world.

Approval-seeking is not that dissimilar to the approval or recognition I think the pilgrim sought from Zhaozhou, that every child wants and seeks from their parents, who are their first experience of gatekeepers, individuals who hold the power to either nurture, assist, and make viable their dreams and aspirations, or to block, find fault with, to hinder them. This dynamic is then extended to our teachers, the football coach, the University admissions board, academic examining bodies, and finally the editors, agents, gallerists, and all those other cultural gatekeepers of the larger social scene; if culture is your thing, if not, transfer that to whatever the realm of aspiration it is for you.

Does my dog have a soul, the pilgrim asks, only to be toppled by Zhaozhou’s Mu. Does this book have a soul, have some universally, or even more narrowly appreciated meaning and worth to anyone other than the writer, to anyone other than the dog owner? Especially if the book, once written, is more than likely going to be placed, with the fanfare that accompanies any self-published venture (i.e. a tweet to my 40 “followers” on Twitter, an email to friends and family) with millions of other books in the featureless, barely visited regions of the Amazon jungle/website, perhaps only to come up if someone does a search on Mu, or Zhaozhou, but even then, the algorithim recognising its self-published nature, possibly not. Does a heterotelic (i.e. made partly for others) project have soul even if no one ever sees or reads it?

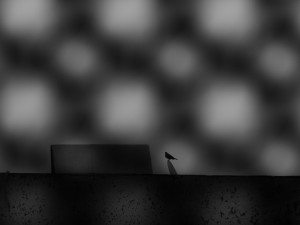

Perhaps I have been thinking about the wrong koan for the last year? Maybe I should have been focusing on the one about the tree, and the events befalling it, and whether those events register for anyone or anything other than the tree, who falls, who now lies vertical where before it stood perpendicular. Does a book that gets written in the forest of the mind, of one person’s consciousness, ever get read if published in the electronic landscape that is really just a larger version of that insular individual’s consciousness, in the bookstore of his mind, or the library, Borges’ Inifinite Library, which is now a real-virtual place: Amazon, the internet? Does a tree growing in the forests of Amazon.co.uk ever get read, ever get a bird to make a home on its branches, or other animals to use it for their enjoyment and comfort? Or does it just exist as a title and a cover jpeg, the facsimile of a tree, pointing at something that happened to someone else, sometime ago, of no interest to you or me?