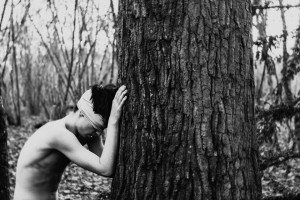

As children, when we feel troubled or inadequate, we turn to an adult, a Wizard, Dad or Mum, in the hope that they might guide, console, or make us whole again. As adults, we continue to look to Wizards such as gurus, therapists, life-coaches, our modern-day Zhaozhous, our parental stand-ins to assist us with a similar kind of emotional alchemy. Frustration, blockage, deprivation within this process can also be an important developmental shift too though. If we’re resilient enough to take it and grow. If not, we call this trauma.

As children, when we feel troubled or inadequate, we turn to an adult, a Wizard, Dad or Mum, in the hope that they might guide, console, or make us whole again. As adults, we continue to look to Wizards such as gurus, therapists, life-coaches, our modern-day Zhaozhous, our parental stand-ins to assist us with a similar kind of emotional alchemy. Frustration, blockage, deprivation within this process can also be an important developmental shift too though. If we’re resilient enough to take it and grow. If not, we call this trauma.

What has kept us reading and rereading The Wizard of Oz for over a century you might say is Baum’s failure to deliver on his initial sunny-side-up promise of pleasure sans heartache or nightmares, but without leaving us with a traumatic experience in the process. Instead the text presents us with just-enough Mu throughout, just enough heartache and nightmares to keep the narrative alive, to keep us soulful and yearning. Has Woo managed to do this for me too?

As I walk to the station, I think of Baum’s Parent-Guru-Therapist figure, his Wizard, a Conchis like figure, though maybe less knowing than Fowles’ Maurice Conchis or my Woo. Baum’s Wizard, Conchis, the Chingford Woo are all agents of frustration, and we wouldn’t want them to be anything else. Had Dorothy and Co., or Nick Urfe for that matter in the Magus, rocked up at the Emerald Palace to find a wise old man embodying the best qualities of Self (calmness, curiosity, clarity, compassion, confidence, creativity, courage, and connectedness) the tale would never have clamped itself, koan-like, onto our imaginations in the way that it has for over a century.

What makes their pilgrimage in search of answers and healing so interesting, and also truth-ringing in terms of our own experience, is that The Wizard is human all too human, the old man fatally flawed, naively child-like in his off-screen demeanour:

“For they saw, standing in just the spot the screen had hidden, a little old man, with a bald head and a wrinkled face, who seemed to be as much surprised as they were.”

Baum’s Wizard, and Conchis, and Zhaozhou, and my Woo (although the latter figures are less disposed to admitting it) are all flawed human beings, “humbugs” as Baum’s Wizard dubs himself, whose only sin is that of propping up through nefarious means their status by not shying away from accepting and encouraging the compelling and influential projections of others onto them:

“Our friends looked at him in surprise and dismay.

‘I thought Oz was a great Head,’ said Dorothy.

‘And I thought Oz was a lovely Lady’ said the Scarecrow.

‘And I thought Oz was a terrible Beast,’ said the Tin Woodman.

‘And I thought Oz was a Ball of Fire,’ exclaimed the Lion.

‘No; you are all wrong,’ said the little man meekly. ‘I have been making believe.’”

In some way, our parents, our therapists, our gurus are also, as we are, “making believe”. And in doing so they may then help us to believe, assisted by important symbolic tokens: the bran and needles that The Wizard presents to The Scarecrow as a representation of the intelligence he has shown to already have; the sawdust-stuffed silken pouch of a heart gifted to kind The Tin Man, the flask of Dutch Courage for the already-brave Lion.

In some way, our parents, our therapists, our gurus are also, as we are, “making believe”. And in doing so they may then help us to believe, assisted by important symbolic tokens: the bran and needles that The Wizard presents to The Scarecrow as a representation of the intelligence he has shown to already have; the sawdust-stuffed silken pouch of a heart gifted to kind The Tin Man, the flask of Dutch Courage for the already-brave Lion.

In this way our Parents, Gurus,Therapists speak to the vulnerable parts of us believing that they might be able to comfort and protect and guide us out of our heartaches and nightmares. But they also often lose and delude themselves with their own “make believe”, becoming self-focused to the point of what may at times appear to be cruel indifference:

“‘This is terrible,’ said the Tin Woodman; ‘how shall I ever get my heart?’

‘Or I my courage?’ asked the Lion.

‘Or I my brains?’ wailed the Scarecrow, wiping the tears from his eyes with his coat sleeve.

‘My dear friends,’ said Oz, ‘I pray you not to speak of these little things. Think of me, and the terrible trouble I’m in at being found out.’”

But is the indifference cruel, or just our next helping of Mu, challenging us to take responsibility for our projections, for our idealised hopes and expectations, our frustrations at those who won’t, but more likely can’t, meet our needs?