What is a puppy, or a young baby for that matter, in his first few months of life, other than a kind of living, breathing Mu?

What is a puppy, or a young baby for that matter, in his first few months of life, other than a kind of living, breathing Mu?

Compared to the adult dog we hope to have our enduring relationship with, the puppy is a bundle of deficiencies: not house-broken; not aware that chew toys are what we do our chomping on (rather than fingers or table legs); not able to be by himself for longer than an hour; not able to control his responses to other people, dogs, objects; not able to walk down the road at your side without bolting.

This is where Mu begins as a kind of refusal. Not in any way consciously or malign motives on the dog’s part, but always present.

When a dog (or a child?) says No, it can feel like a sundering of some kind of contract. Which perhaps reads something like this: you’re needy, I have what you need, so I take care of you, but in return for that, I require a certain level of obedience with regard to my wishes. You do what I say.

This is also the deal that God struck with his Chosen Puppies. I am the Lord thy God, thou shalt have no have no other Gods before me etc. In man-puppy parlance, if this is also the first commandment, the second being: sit! And then: down!

This is also the deal that God struck with his Chosen Puppies. I am the Lord thy God, thou shalt have no have no other Gods before me etc. In man-puppy parlance, if this is also the first commandment, the second being: sit! And then: down!

This is how it plays out in the first few weeks: in fear and anger.

1. FEAR

8.30 pm

I am trying to meditate, whatever that means, in the lounge, with you Max consigned to your little “cave”, your Mommy-less lair that I’ve made for you in the bedroom with chicken wire partitions and a pillow/doggy-blanket/soft-toy stuffed crate.

I have designed it this way as a safe space where you can be kept in those hours of the day when I’m taking care of clients, or for the occasional 20 minutes I need to sit quietly with myself, doing this thing I still call meditation. This thing I’ve been somewhat erratically doing since my early 20s when I took up the challenge in a somewhat portentously serious way via Michele and his Centro Zen.

You have been whining incessantly for about 10 minutes now. Each whine cuts like a nerve-shredding buzzsaw into my fragile equanimity. I can hear you scrambling and pawing at the bamboo, chicken-wire, and paint-pot structure I’ve erected to stop you from getting into the rest of the bedroom, from chewing your way through whatever footwear has been left on the floor, gnawing holes in socks, or sampling with teeth and lips and tongue the spines of books on the shelves or the bedside table.

Even though this is only our second week together, you already know that I don’t have company with me in the room next, know that my last client for the day has departed, and you cannot understand why this doesn’t automatically grant you access to me again. For you, it’s a very simple equation: you want to be where I am. I understand this all too well: your attachment-seeking limbic system tells you that you should be right there next to me, and for some reason this ain’t happening. So sound the alarm!

Even though this is only our second week together, you already know that I don’t have company with me in the room next, know that my last client for the day has departed, and you cannot understand why this doesn’t automatically grant you access to me again. For you, it’s a very simple equation: you want to be where I am. I understand this all too well: your attachment-seeking limbic system tells you that you should be right there next to me, and for some reason this ain’t happening. So sound the alarm!

Your every whine is not only communicating this overwhelming need to stay attached, but also in some way testing our bond, testing to see how much this caregiver can bear to be loved, and also how much I can bear to love you back.

A puppy wants to love its mother with all its bodily powers, writes Anna Freud (quoted in a letter from Melanie Klein to Marion Milner, in which I suspect Klein made up the quote as I can find no other attribution for it). This is a description of a truly voracious love, an all-consuming, symbiotic love (mutualism, commensalism, even parasitism) which we now largely think about in relation to the child or a puppy’s staged development, this first stage being one of Attachment.

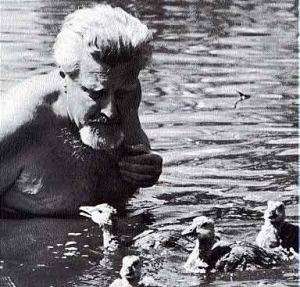

Attachment is a concept that John Bowlby took from Konrad Lorenz’s cross-species daddying of his gosling chicks. Konrad used the somewhat unlovely term of “imprinting” to describe this state of affairs (but you only have to look at the pictures of him and the goslings to see that there is so much more going on here).

Attachment is a concept that John Bowlby took from Konrad Lorenz’s cross-species daddying of his gosling chicks. Konrad used the somewhat unlovely term of “imprinting” to describe this state of affairs (but you only have to look at the pictures of him and the goslings to see that there is so much more going on here).

Bowlby brought Konrad’s pied-piper ethology back into the human dyad, with the idea of an imprintable attachment, this “lasting psychological connectedness between human beings” as he defined it, guiding almost everything we do as infants, but then also having an unconscious but critical impact on our adult relationships.

Our attachment behavioural system (our first and purely behavioural form of love?) initially works to maintain or achieve proximity to attachment figures, usually one’s primary caregivers, providers of continuous safety and nurturing. This is why babies and puppies cry, actually scream, when they feel unsafe, or uncomfortable, as if they were being murdered, which is probably how it feels to them, and certainly how our mirror neurons pick up on the message they’re sending.

In our first week together, Max, I would often take you out with me in the mornings to the summer house where I’d try and do some writing on this text while you’d try to get into the raised beds to cause havoc. Once, I left you for a few minutes to go and get a cup of tea. As the kettle boiled from 30 metres away, a siren-like screech assailed my ears, loud enough to fill Wembley stadium with its urgent howling appeal. I couldn’t believe that this tiny ball of fur, who up to this point had made a sound no louder than a bird’s cheep, had this volume and sonic force within him.

In our first week together, Max, I would often take you out with me in the mornings to the summer house where I’d try and do some writing on this text while you’d try to get into the raised beds to cause havoc. Once, I left you for a few minutes to go and get a cup of tea. As the kettle boiled from 30 metres away, a siren-like screech assailed my ears, loud enough to fill Wembley stadium with its urgent howling appeal. I couldn’t believe that this tiny ball of fur, who up to this point had made a sound no louder than a bird’s cheep, had this volume and sonic force within him.

It is a sound that instantly communicates the terror of a small and defenceless creature being attacked and devoured by a larger one. This isn’t happening of course, but your attachment system, designed to hypervigilantly monitor safety and security levels, had no doubt been triggered by some kind of ambivalence or threat in that sphere and so instinctively kicked in with his stress-fueled, blood-curdling wail, creating a kind of towering Louise Bourgeoisesque sound sculpture.

This acts as a worst-case-scenario foretelling or warning for the me, the caregiver who has perhaps absent-mindedly wandered off for a moment. The alarm communicates that unless I return to the vulnerable creature post-haste, there might not be a child or puppy to return to. In fact, the first thought I had when I heard his screeching was that maybe a fox had gotten into the garden and was trying to carry you away.

This acts as a worst-case-scenario foretelling or warning for the me, the caregiver who has perhaps absent-mindedly wandered off for a moment. The alarm communicates that unless I return to the vulnerable creature post-haste, there might not be a child or puppy to return to. In fact, the first thought I had when I heard his screeching was that maybe a fox had gotten into the garden and was trying to carry you away.

What might this have to do with Mu or meditation you might ask?

Well, maybe everything. A lot of people who seriously throw themselves onto this kind of path, seem to have had some kind wounding in their early attachments, some kind of Mu-injury. Perhaps that of getting too little of what they needed as infants (deprivation), or too much (intrusion). Or maybe something unpredictably, and confusingly in-between.

We are all born with core needs and our caregivers will thus fall along a continuum of either attunement to those needs, or some kind of jangling misattunement. Mu being a way of summing up the latter perhaps?

The Buddha’s own mother died shortly after childbirth. So we might ask the extent to which he would have got his needs met from a preoccupied father, leader of the Shakya clan, who was also mourning the loss of an attachment figure in his wife Maya. Or for that matter from his new mothering stand-in, the unfledged younger sister, his aunt Pajāpati, who had no choice but to take on the burden of caregiving, but perhaps before she was ready to do so.

The Buddha’s own mother died shortly after childbirth. So we might ask the extent to which he would have got his needs met from a preoccupied father, leader of the Shakya clan, who was also mourning the loss of an attachment figure in his wife Maya. Or for that matter from his new mothering stand-in, the unfledged younger sister, his aunt Pajāpati, who had no choice but to take on the burden of caregiving, but perhaps before she was ready to do so.

This is a man who would grow up to formulate a whole way of being based around a kind of Mu-deprivation. He called it The Four Noble Truths which forms the foundation of Buddhism, and which I first came across under the tutelage of Michele and acolytes all those years ago.

When I hear Max yelping in the other room for me as I sit and meditate in the other room, he too is perhaps coming to grips with these four knotty truths (I’m not sure what makes them “noble” per se), although like most of us, he is probably only conscious of the first.

This being:

1) Life contains discomfort and deprivation, aka suffering: “I want to be there with my primary attachment figure instead of here in my crate. As a socially-evolved creature, it hurts to be alone.”

Now the other three. As Max might voice them, if he could:

2) “There is a reason for why I’m feeling puppy-panicky. You’re there, I’m here, and what that Mu does to me, which I attribute as you doing to me, feels ruinous, cruel, and devestating.”

3) “If there is an explanation for this feeling, then there is maybe also a way to cope with it. Such as learning how to tolerate and be OK with Mu (in this case the frustration of not being with you).”

4) “Putting an end to this Mu-suffering, for me as a dog, will hopefully occur as I get adequately-but-not-unremittingly frustrated by caregiver, who fundamentally wants to do right by me, and hopefully has the parenting skills to do so.

If this were an educational video on YouTube, maxi kitted out in white coat and rimless spectacles (scientist gear) would step in at this point and deliver some further teaching.

“That’s right, little buddhas, and now, with the wonders of neuroscience, we also know that this optimal frustration should aid in the development of your ventro-medial prefrontal cortex (vmPF) which accounts for about 1/10th of my doggy brain, and much more in humans. For both of us, our vmPFs are required to self-soothe and regulate our emotions. This helps especially when Mu feels like it’s turned maniacal and is cleaving us into a thousand painful pieces. In the human brain, the vmPF takes up almost a third of cerebellum real-estate. In cats its just 1%. (Poor, deluded cats.)

“But also poor, insecurely-attached adult humans who didn’t get what they needed from their primary caregivers and so sometimes feel, when triggered in relationship with other human beings, as if they’re being ripped apart limb by limb by a merciless predator.

“What can they do?

“Well, the Buddha, ur-psychologist that he was, had a treatment plan for his and others’ early attachment wounds which he called The Noble Eightfold Path. The Buddha was not only a psychologist, but also a canny marketeer, as all his self-helpery was, as you can see, framed as “Noble”. My caregiver on the other hand is going to try and get his healing done via a writing and koans.

“Or to put that in dog-speak: on a wing and a prayer, a bone, a yelp, and a shelf of musty paperbacks with tasty looking spines.”

2. ANGER

We are in Queensbury Park, the site of many a showdown I will discover over the next year.

I have my foot on your lead, pinning you down close to the ground. We are on the far corner of Queensbury Park, closely watched from afar by three bemused Romanian labourers sitting on a park bench.

I shove kibble at your face, then pieces of cooked liver. Each time I do this, you growl, yelp, make as if to bite my hand. Between your jaws, something, I’m not sure what, sounds like a piece of bone, the knuckle of a drumstick, or maybe the triangular wedge of a chop, the pen-drive-shaped rectangle of rib. Whatever it is, you’re working away on it like a koan.

Normally I can get my hands into your mouth without injury but this time I fear I’ll get bitten if I try. I hold you down, stare you down, wait. You don’t let up for a moment, chewing in a series of furtive, erratic jaw clamp-downs. You won’t be bribed away from his treasure, nor bullied or cajoled. This is you asserting your own very mighty Mu in the shape of “I want this thing and I will not give it up.”

Finally, you swallows.

I am enraged – a red hot coal of anger bouncing around my chest, shoulders, and in the explosive space between my ears, sparks flying everywhere.

Why am I so surprised by the ferocity of your desire for this scarce resource? You don’t get this kind of treif at home from me, which is what makes it even more delicious when you find a bit of it in the park. Kibble, liver (lovingly slow-cooked in the oven with organic olive oil), little pieces of pecorino cheese, that’s all yawnsomely kosher. But rib, chicken, chop, an unforbidden meaty trinity, nothing can compare to their pull.

Why my surprise at the unassailable force of your curiosity and desire, Max? When desire of this nature manifests in narrative, we call it it passionate, romantic, or ambitious, even if vaunting: the one who goes all out to have the craved-for other, or thing. But when it manifests in a puppy or a child, a creature we have made a unilateral contract to look after as long as they continue to cede us the upper hand, this feels obstructive. Which it is. The contract being based on this tiny, helpless creature always saying “Yes”.

Sit! (yes). Down! (yes) Come here? (yes) Urinate! (yes) Walk at the correct distance beside me on a lead without stopping to investigate interesting objects in your path (yes).

So when the basis of this contract is broken with your Mu, the result is an obstruction, a restriction, a hindrance to the smooth flow of gratifying yeses the fantasy of having a dog suggested were all within reach. Anger is an adaptive way of dealing with obstructions. Anger fills the body with energy-ramping neurochemicals (adrenaline, cortisol, norepinephrine) gearing us to wrangle, scrap, skirmish, contest. To push through or over or beyond whatever is standing in our way. The only problem is that if this is a small puppy or a child, who is being unregulated not because they are deliberately disobeying us, but because this is their way of exploring and testing boundaries, anger is not a useful emotion to have driving the tank. I am learning this in a very clunky and maladroit way, the way all parents learn perhaps.

Little did I realise that when you arrived Max that this would be the koan you would bring with you. You might say it is the koan, all children present to their parents at some stage in their development: “Can you tolerate frustration without exploding? Can you tolerate Mu? Can you? Show me how please, because my life depends on it.”